WPF MenuItem as a RadioButton

It seems that there is not a MenuItem that works as a RadioButton that allows only a single selection that is in WPF. So I set off to figure out the best way to do this in WPF.

So let me go ahead and put the final solution right here on top. Then I will walk you through how I arrived at this solution. I researched a lot of solutions and none of them were this solution. I had to figure this one out myself and I am glad I did because this one is the shortest and sweetest solution yet.

Here is a project showing how to do this with two examples, one directly in the MainWindow.xaml and one as its own class.

MenuItemWithRadioButtonExample.zip

Here is the code for creating a class that just works as a MenuItem with a RadioButton.

<MenuItem x:Class="MenuItemWithRadioButtonExample.MenuItemWithRadioButton"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Header="RadioButton Menu" >

<MenuItem.Resources>

<RadioButton x:Key="RadioButtonResource" x:Shared="false" HorizontalAlignment="Center"

GroupName="MenuItemRadio" IsHitTestVisible="False"/>

</MenuItem.Resources>

<MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="MenuItem">

<Setter Property="Icon" Value="{DynamicResource RadioButtonResource}"/>

<EventSetter Event="Click" Handler="MenuItemWithRadioButtons_Click" />

</Style>

</MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

</MenuItem>

Then you need to add the MenuItemWithRadioButtons_Click event method to your code-behind as well.

private void MenuItemWithRadioButtons_Click(object sender, System.Windows.RoutedEventArgs e)

{

MenuItem mi = sender as MenuItem;

if (mi != null)

{

RadioButton rb = mi.Icon as RadioButton;

if (rb != null)

{

rb.IsChecked = true;

}

}

}

Note: Since this even code involves the View only, this doesn’t break MVVM. With MVVM it is allowed to put code in the code-behind as long as it is code only for the View.

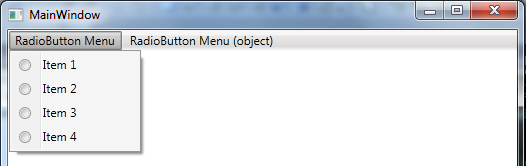

This works quite well and I am quite happy with it. Here is how it looks

Attempt 1 – A RadioButton in MenuItem.ItemsTemplate

Result = Failed!

I changed the MenuItem.ItemsTemplate, as follows.

<MenuItem.ItemTemplate>

<DataTemplate>

<RadioButton Content="{Binding}" GroupName="Group" />

</DataTemplate>

</MenuItem.ItemTemplate>

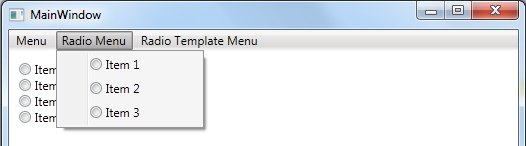

This almost worked, but it wasn’t quite right. It turns out that anything in the DataTemplate is actually boxed inside a MenuItem, so it left a space. Look at this screen shot.

Notice there is a square space on the left, then a slight separator, then our RadioButton. We need the toggle to be in that empty box, and only the text to be on the right. Also clicking on the empty box doesn’t click the RadioButton.

So I need to figure out how to make it not be boxed in a MenuItem. It might be possible to find a way to make the DataTemplate not be boxed in a MenuItem, but I researched this and decided it wasn’t the best way to go.

Attempt 2 – A RadioButton in MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle

Result = Failed!

In my second attempt, I attempted to change the ItemContainerStyle.

<MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="MenuItem">

<Setter Property="Icon">

<Setter.Value>

<RadioButton HorizontalAlignment="Center" GroupName="MenuItemRadio" />

</Setter.Value>

</Setter>

</Style>

</MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

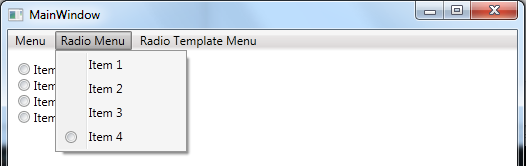

This didn’t work either. Look at this screen shot.

It seems that only one instance of the RadioButton was created on so only the last item it was applied to actual showed it.

It had a second issue in that the RadioButton didn’t actually have any content. This might be a problem if you are hoping to use the Content in a click event. It seems that both MenuItem.Header and RadioButton.Content should be the same value, but only the MenuItem.Header should display.

The third issue was that the RadioButton is only toggled when clicking directly on the RadioButton, but not when clicking on the text or “Header” portion of the MenuItem.

The fourth issue is that when clicking the RadioButton the menu stays open even if StayOpenOnClick=”false” is set.

Attempt 3 – An unshared RadioButton in Resources used by MenuItem.ItemsTemplate (Success)

While it didn’t work the first time, this method had promise. Step two got me close, but left me with three problems to solve.

- I needed to figure out a way to not have the MenuItem elements share the RadioButton and that didn’t take long to research and resolve. I just needed to declare the RadioButton outside the Style and then use a StaticResource to bind to it.

- I needed to add an event to have the MenuItem click pass the click on to the RadioButton. That was easy enough.

- I needed to make it so the Menu would close when clicking directly on the RadioButton. I actually just set IsHitTestVisible=”false” on the RadioButton, because we already made just clicking the MenuItem work in problem 2.

- I had to change the RadioButton’s Horizontal Alignment to Center to make it look best.

So here is a screenshot so you can see it looks just how you want.

Check out the Xaml and event method as well as the example project at the top of this page.

Note: If you need to make the MenuItem.Header and RadioButton.Content share the same value, then do this:

<MenuItem x:Class="MenuItemWithRadioButtonExample.MenuItemWithRadioButton"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Header="RadioButton Menu" >

<MenuItem.Resources>

<RadioButton x:Key="RadioButtonResource" x:Shared="false" HorizontalAlignment="Center"

GroupName="MenuItemRadio" IsHitTestVisible="False">

<RadioButton.Content>

<Label Content="{Binding Path=Header, RelativeSource={RelativeSource FindAncestor, AncestorType={x:Type Window}}}"

Visibility="Collapsed"/>

</RadioButton.Content>

</RadioButton>

</MenuItem.Resources>

<MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

<Style TargetType="MenuItem">

<Setter Property="Icon" Value="{DynamicResource RadioButtonResource}"/>

<EventSetter Event="Click" Handler="MenuItemWithRadioButtons_Click" />

</Style>

</MenuItem.ItemContainerStyle>

</MenuItem>

Notice that Visibility=”Collapsed” is set, as we don’t need both the MenuItem.Header and the RadioButton.Content to display. I thought I needed this, but it turned out I didn’t. Still, I thought I would share it anyway.